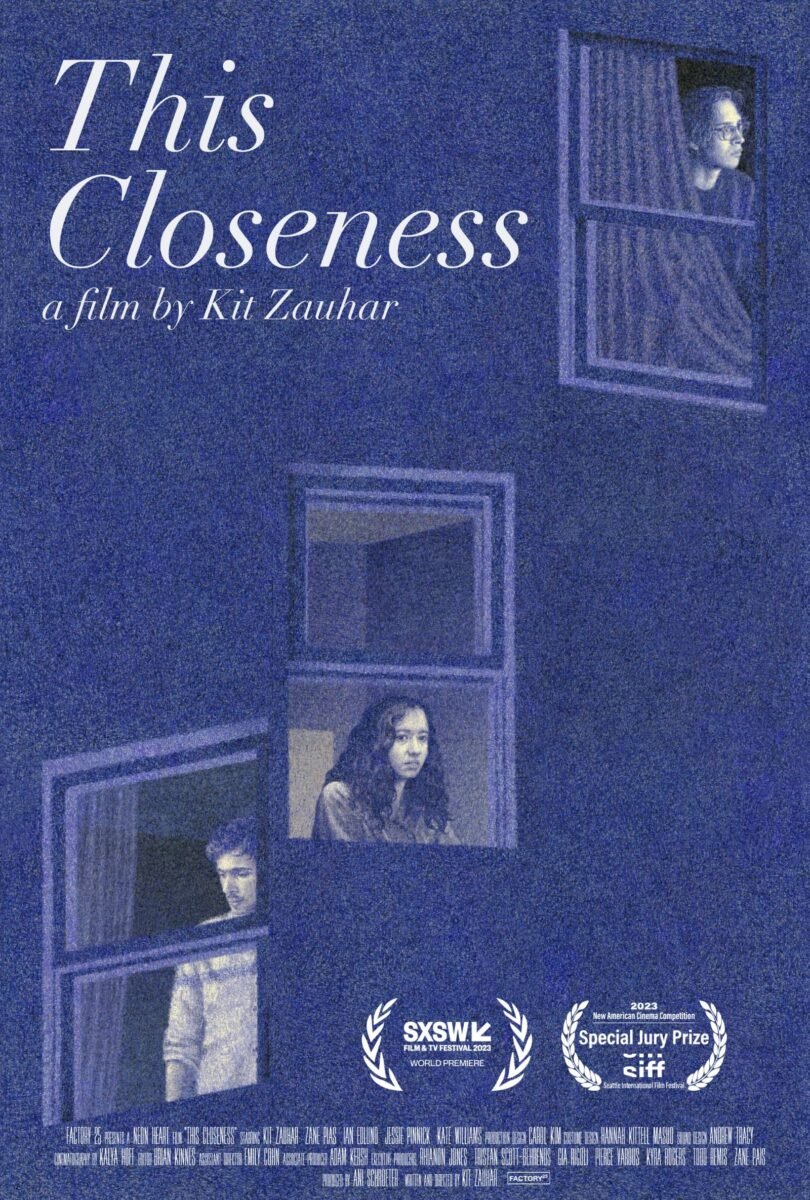

Kit Zauhar on the Depiction of Intimacy in Her New Film, This Closeness

Filmmaker Kit Zauhar, a rising talent in the film industry, brings forth a raw and honest portrayal of toxic relationships in her new film This Closeness, serving as director and writer of a poignant, SXSW selection. Though, in addition to her title as the project’s visionary creative, Zauhar also challenges herself by stepping into the role of the film’s cautious lead, Tessa.

Inspired by her personal experiences and identity as a young bi-racial woman, Zauhar masterfully uses the film to spotlight recurring themes of race relations and interpersonal dynamics through a story that deconstructs modern traits of intimacy and sexual desire — which, prior to This Closeness, has also earned the filmmaker praise for her widely-celebrated debut film Actual People. So at this point (after cultivating two praiseworthy hits), it’s clear that Zauhar is working her way towards becoming a next-gen creative who’s guaranteed to thrive.

With the film out now (courtesy of IFC) we had the opportunity to speak with the visionary artist about her intentions with This Closeness, the central couple’s relationship, toxic masculinity, weaponizing intimacy, and much more.

Congratulations on releasing This Closeness – a project that’s essentially your incredible vision come to life! What initially led you to write, direct, and star in a film that explores intimacy and vulnerability in such a unique way?

Kit Zauhar: Thank you! This is essentially a film about intimacy as a tool instead of a concept in a more therapeutic/safe sense. Intimacy is used throughout the film as a weapon, a method of manipulation, a trap, and even a means of monetization [like with Tessa doing ASMR]. I think a lot of people see intimacy as this sort of end-all-be-all, once it's achieved what exists ahead is this soft, warm space where only good feelings can be had moving forward, which is really not how I've ever viewed it because people are fickle, and sometimes cruel, or other times really just self-involved and clueless, and that leads people to deform intimacy, wear it as a mask, or use it to hurt someone close to them.

I think of This Closeness as a petri dish for all of these ideas and interactions I was interested in exploring. I also like the combination of a contained environment and strangers; it's something that you see across my work and also harkens back to a lot of classic as well as contemporary theater (Hell is other people). I think vulnerability can be a byproduct of intimacy, but I never really write characters with the intention that they'll "be vulnerable" from the start. I want to see if it feels emotionally logical for them to be so. I also want to make a delineation between a performer being vulnerable to service a character as opposed to a character being vulnerable. For instance, I see Tessa as not so vulnerable. Sure, we see her having therapy, we see her having sex, but she's in control of the situation; she's articulate of her desires and in many ways getting those desires, even if she's struggling with them. I as a performer made myself vulnerable, but that doesn't necessarily translate to character. Obviously, Adam and Kristen's characters are vulnerable, as were the performers to achieve that confluence. I don't think I make such a conscious decision when I'm working on something if I am going to wear all three hats on set; it usually just feels organic to do so.

As a multi-hyphenate creator, how did your previous work influence the storytelling and vision of This Closeness?

Kit Zauhar: I think coming from a theatrical background had a big influence on this. I was originally writing this as a stage play during the pandemic, but then I had the realization that there was a long future ahead of me in which live theatre might not be a possibility, so I decided to make it a film. I think I've always been interested in the same ideas as my work going back to when I was in high school, maybe earlier: strangers connecting, messy interpersonal relationships, the dynamics between white men and women of color, and, my identity as a bi-racial woman. These have been at play in various combinations. I think this film feels like a refinement of the Kit Zauhar formula that I've been experimenting with throughout my life. There is a concentration to this in terms of themes, dynamics, and, obviously, characters.

What were some of the key inspirations behind these characters and the personalities they represent?

Kit Zauhar: Ben and Adam represent parallel experiences of white toxic masculinity. Both of them have an innate power and an innate higher social standing in the world than any of the other characters in the film. They have leverage both in personal relationships and, more broadly, in society, but Ben chooses to wield it and use it in ways that are both trivial and have more serious consequences. Adam, on the other hand, has these same advantages in his reach but has difficulty understanding how to use them, or a fear or general ineptitude of using them, most of the time opting to play a more passive participant in this world. However, as we know, he does end up using his power in a really uncouth, and, some could argue, more detrimental manner than Ben has throughout the course of the film. I think people know these characters even if they haven't personally encountered someone in the real world exactly like Ben, Tessa, Adam, or Lizzy. They're not exactly archetypes, but they feel representative of our milieu of younger millennials whose personalities have been shaped by history and its consequences, contemporary culture, and its personalities.

This Closeness | Factory 25What do you believe the film communicates about the blurred boundaries between connection and possessiveness in relationships?

Kit Zauhar: Ultimately Ben and Tessa have a pretty toxic dynamic, one that is judgmental, and not fully safe, but within that there is immense excitement and a compelling volatility, that intimacy is not a soft cushion but a battleground where one can emerge victorious over and over again. I think when a person does not feel like they fully "have" a person intimacy is weaponized to try and make someone "belong" to someone else. What's interesting is that both Ben and Tessa seem equally willing to be had and have the other person, so really it's kind of just a mind game they play to keep things interesting, which is what people who should not be together but end up doing to fill some parts of their relationship that would feel hollow or discontented otherwise.

I’m fascinated that as a filmmaker, you balance the emotional intensity, humor, and even tense psychological aspects of these characters! Did you always envision the film crossing over into so many territories – or did that take shape over time?

Kit Zauhar: When you write something with an emphasis on naturalism and dialogue you'll usually end up with something that crosses into different genres and plays with humor as well as sadnesses because that's how most people and most conversations operate. For instance, I went upstate with some close friends for the eclipse, and, as it usually happens, we ended up having a wide array of conversations ranging from incredibly silly riffing and shit-talking to getting really deep about family, past trauma, you know, all that stuff. I think when people spend a lot of time together, and a lot of that time talking, as they do in my movies, it's nearly impossible to keep them on one note.

Another example of this that really sticks out to me was after my grandfather died we had a small funeral service for him at the church near my childhood home in Philly, and afterward my family and a few friends, and a few nuns from the church went to a Vietnamese restaurant, which felt kind of random but was really good, and we ended up having this really lighthearted, sometimes insanely funny, conversation. I was only eleven or twelve, I think, but I remember being wonderfully shocked by this turn of events. But that's human nature, we think deeply and mournfully, and we also laugh a lot, and both are tools of survival and enlightenment. That's the beauty of language, of dialogue, that it is really this, like, chimera we make of parts known and unknown we are constantly arranging and messing with just by continuing to talk and understand each other.

The final scene leaves audiences curious about the next moments and how, or if, this weekend has changed anything about Tessa moving forward. Did you have your own idea about the next chapter for Tessa and Ben, or is that something that you’ve always viewed as open-ended?

Kit Zauhar: I don't believe in character backstories or epilogues if they're not written; As you can imagine I'm not into fan-fiction or "endings explained." I, too, left the characters exactly where the audience last sees them and I don't really have an idea what happens next. My intention was to write a contained piece, from when they enter the Airbnb to when they leave; after that, the characters don't really exist for me, nor do I really want them to. I also really wonder, has Tessa changed, or has she just, however temporarily, had to confront conflicts and faults within herself that are unsavory and that's dampened her spirits?

I mean, I don't see any of the characters in this film being capable at this stage of his/her life with a revelation, and I think in general my films are sort of anti-revelation – unless I make this decade-spanning epic in the future, then we'll see. People don't really change much, especially not over the course of the weekend. Perhaps they learn more about themselves, but I'm under the impression they're relearning things they already knew, but just don't want to acknowledge because it's painful, because it's embarrassing, because it means having to change when changing is so, so difficult. I think along with the classic "hell is other people," there's the implication that no one is going to save you from other people, but also, no one is going to save you from yourself.

In closing, is there something you’d like audiences to take away from their experience with This Closeness concerning their own lives?

Kit Zauhar: Unfortunately I am as anti-takeaway as I am anti-revelation. I suppose the goal of art is to walk away from the experience feeling more open, and more empathetic to the world, like your heart is trying to push itself out of your chest. That's always the goal, regardless of what's being made. But, I don't know if I have any sort of moral or ethical statement to make. Don't share an Airbnb if you can afford not to...? Maybe stay with friends? I went to my high school reunion – which obviously served as some inspiration for this – in between filming and this release and I learned that unlike maybe 90% of my class I did not have the funds to buy real estate, which I should probably work on. Invest in real estate! So you don't have to share Airbnbs and you can flex on people who think they're so cool because they live in Chinatown and make movies – me – at your high school reunions!